In our side-bar to the right we have a section for "Upcoming Meetings and Events." Sadly, it is often empty. Perhaps as a result of the anechoic effect, there seem to be few talks, workshops, much less symposia, conferences, and courses on the issues we discuss on Health Care Renewal.

However, I am happy to now note two upcoming events of interest.

First, and most directly related, is the 2011 PharmedOut.org conference, entitled, "Pharma Knows Best? -Managing Medical Knowledge," on 16-17 June, 2011 at Georgetown University in Washington, DC, USA. PharmedOut.org is dedicated to addressing how pharmaceutical companies seek to influence medical decision making.

My editorial comment is that pharmaceutical companies, and also biotechnology, device, health care information technology, and health insurance companies spend billions on marketing to try to influence health care professionals and patients to use their products just here in the US, and probably hundreds of millions on public relations to try to influence policy-makers in favor of their interests. The amounts spent to educate health care professionals and the public about these efforts, and particularly about deceptive marketing and PR, stealth marketing and stealth advocacy campaigns, etc, is minuscule by comparison. PharmedOut.org is one of the few organizations trying to address the hype and spin.

Second is the Transparency International Summer School on Integrity, to be held in Vilnius, Lithuania, on 11-15 July, to provide "intensive anti-corruption training for future leaders." Unfortunately for the rest of us, enrollment appears to be restricted to "students, graduates, and young professionals" from the post-communist countries.

My editorial comment is that despite the prevalence and importance of health care corruption, as documented by the 2006 Transparency International Global Corruption report which focused on health care, and of the importance of conflicts of interest as risk factors for corruption, there are very few opportunities to teach and learn about these issues anywhere in the world. (As I once noted, I could only find a single course on health care corruption and related issues in any US university.) Transparency International has a record of efforts made to directly fight corruption, and to teach about related issues. Would that such courses be available all over the world.

Friday, March 11, 2011

Is Microsoft slowly edging towards an "exit stage left" in health IT?

Interesting item seen here:

Why would this not surprise me if true?

Because I predicted it.

In July 2006, nearly 5 years ago, in my July 2006 post "Bill, Have You Lost Your Mind?"

Nobody was listening, just as nobody seems to be listening to my current dire predictions for the National Program for IT in the HHS™ .

Wait until 2016...

-- SS

From Dabney: “Re: former Sentillion exec departures from Microsoft. Microsoft transferred their 800 Health Solutions Group people into the small-to-medium commercial sector group (Microsoft Business Solutions) last Monday. Peter Neupert and his whole organization have been pushed out of the incubation group in Microsoft Research with the guys who sell Microsoft Axapta ERP and CRM for small commercial customers. That will mark the end of acquisitions and spending of Microsoft on health because they haven’t had any significant sales of Amalga UIS in the past year after already withdrawing Amalga HIS and Amalga RIS/PACS from the market. Microsoft is slowly edging towards an exit stage left in health IT.

Why would this not surprise me if true?

Because I predicted it.

In July 2006, nearly 5 years ago, in my July 2006 post "Bill, Have You Lost Your Mind?"

Nobody was listening, just as nobody seems to be listening to my current dire predictions for the National Program for IT in the HHS™ .

Wait until 2016...

-- SS

Thursday, March 10, 2011

A New Venue From a Surprising Source to Discuss "External Threats to Good Decision-Making"

A new blog, entitled the Medical Professionalism Blog, signed on last week with a post emphasizing some themes that should be familiar to Health Care Renewal readers:

So, our new colleague in the blog-sphere raised the following questions:

Again, the importance of threats was emphasized, and concerns about conflicts of interest affecting physicians' professionals were implied. This blog will apparently have a unique focus which I hope will complement our approach on Health Care Renewal.

So we welcome The Medical Professionalism Blog to our blog-roll and look forward to some interesting content.

For a final twist, I need to note that this blog's authorship appears to be unique. The Health Care Renewal bloggers, and most of our blogging friends mostly seem to include, in no particular order: academic physicians, often tenured or retired (and thus able to speak more freely), other generally senior or retired academics, independent or retired practicing physicians, journalists, independent consultants, some whistle-blowers and others who once worked in the health care establishment, and some very anonymous bloggers in the belly of the beast. Thus, we are generally an very independent and iconoclastic, if a somewhat rag-tag lot.

However, the chief blogger on The Medical Professionalism Blog is Daniel Wolfson, who is Executive Vice President and Chief Operating Officer of the ABIM (American Board of Internal Medicine) Foundation, and the blog itself is a project of the foundation. Thus, this is a blog from the heart of the medical establishment, the powers that be, etc, etc. No other blog on our blog-roll comes from a current leader of such an organization. (One is written by someone who was a CEO of a major academic medical center/ hospital system, but who lost his job under controversial circumstances.)

It is truly refreshing to have a voice coming from the inside, so to speak, proclaim:

Furthermore,

Lately, we have not heard a lot of calls for vigorous debate and dissent from the medical establishment, the powers that be, etc, etc. In fact, the anechoic effect is how we describe how such debate and dissent has been suppressed.

So it appears the The Medical Professionalism Blog may be a real breath of fresh air. We hope it can truly inspire some discussion, especially open discussion of issues which used to be not what one was supposed to talk about in polite health care company. This could help advance the transparency which we have long been advocating.

There is an increasing focus on the sustainability of the U.S. health care system based on current cost trends. Predictions are for the health care system to consume 19% of the GDP by 2019. How did we get here?We have been underlining concerns that health care professionals' values, the mission of academic medicine, and truly evidence-based practice are under a series of threats. (For a recent, but already out of date list of threats to the academic medical mission, see this post.) It is nice to see that that others are now alarmed by these threats and looking for ways to counter them.

Some point to the overuse and misuse of health care services, inefficiencies and lack of care coordination. Others blame the lack of clinical evidence, primary care workforce and the external threats to good decision-making, such as a toxic payment system and the influence of pharmaceutical and device companies.

While there are many different ideas about what got us here and what should be done, there is wide consensus that physicians and other stakeholders must begin to develop new more effective and efficient systems of care and make wise choices that preserve our health care system’s sustainability.

So, our new colleague in the blog-sphere raised the following questions:

* What is the appropriate role of physicians and other stakeholders in preserving these resources?

* What behaviors foster and which threaten wise choices in medical decision-making?

* How can waste be removed from the system without sacrificing quality or safety?

* What system changes are needed to achieve better health care outcomes, reduce costs and improve the patient experience?

* What effect do the nature and performance of partnerships – clinician-patient, clinician-organization and clinician-society — have on professional behaviors and resource use?

Again, the importance of threats was emphasized, and concerns about conflicts of interest affecting physicians' professionals were implied. This blog will apparently have a unique focus which I hope will complement our approach on Health Care Renewal.

What we’re hearing from folks is the need to 'show me how' to answer these questions. Through analysis of promising practices, we hope to provide examples of what works – and what doesn’t.

So we welcome The Medical Professionalism Blog to our blog-roll and look forward to some interesting content.

For a final twist, I need to note that this blog's authorship appears to be unique. The Health Care Renewal bloggers, and most of our blogging friends mostly seem to include, in no particular order: academic physicians, often tenured or retired (and thus able to speak more freely), other generally senior or retired academics, independent or retired practicing physicians, journalists, independent consultants, some whistle-blowers and others who once worked in the health care establishment, and some very anonymous bloggers in the belly of the beast. Thus, we are generally an very independent and iconoclastic, if a somewhat rag-tag lot.

However, the chief blogger on The Medical Professionalism Blog is Daniel Wolfson, who is Executive Vice President and Chief Operating Officer of the ABIM (American Board of Internal Medicine) Foundation, and the blog itself is a project of the foundation. Thus, this is a blog from the heart of the medical establishment, the powers that be, etc, etc. No other blog on our blog-roll comes from a current leader of such an organization. (One is written by someone who was a CEO of a major academic medical center/ hospital system, but who lost his job under controversial circumstances.)

It is truly refreshing to have a voice coming from the inside, so to speak, proclaim:

The Medical Professionalism Blog was created by the ABIM Foundation to stimulate conversation and highlight best practices related to professionalism....

Furthermore,

Open for considerable debate is my belief that physicians’ engagement in quality, safety and the management of health care resources ultimately improves the care they give their patients and adds to their joy of work. I look forward to hearing your point of view, even if it’s a dissenting one.

Lately, we have not heard a lot of calls for vigorous debate and dissent from the medical establishment, the powers that be, etc, etc. In fact, the anechoic effect is how we describe how such debate and dissent has been suppressed.

So it appears the The Medical Professionalism Blog may be a real breath of fresh air. We hope it can truly inspire some discussion, especially open discussion of issues which used to be not what one was supposed to talk about in polite health care company. This could help advance the transparency which we have long been advocating.

Wednesday, March 9, 2011

ONC: "The Benefits Of Health Information Technology: A Review Of The Recent Literature Shows Predominantly Positive Results"

The Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT in the US (ONC) has just published an article in "Health Affairs" entitled "The Benefits Of Health Information Technology: A Review Of The Recent Literature Shows Predominantly Positive Results", Buntin, Burke, Hoaglin and Blumenthal, Health Affairs, 30, no.3 (2011):464-471, doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0178.

It is available at the hyperlink above, but may not be publicly accessible.

The authors all are, or were, ONC officials:

The abstract is as follows:

I have long stated, at least since 1999, that:

The new ONC review article is certainly pointing in this direction. Perhaps Health Affairs will release it to general circulation.

However, I also wrote:

Whether the new ONC article demonstrates that these issues are starting to approach resolution, or is just another opinion paper not fully supported by facts, is not certain.

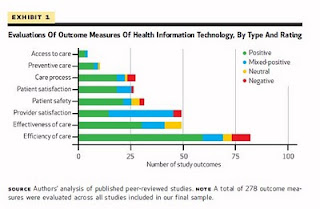

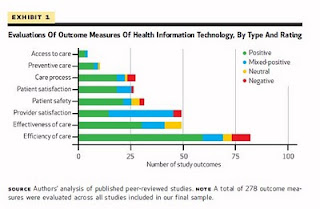

Two charts are presented that summarize the findings (click to enlarge):

(Click to enlarge.) Evaluations Of Outcome Measures Of Health Information Technology, By Type And Rating

(Click to enlarge.) Evaluations Of Outcome Measures Of Health Information Technology, By Type And Rating

(Click to enlarge.) Health Information Technology: Study Design And Scope Factors Associated With Positive Overall Conclusions

(Click to enlarge.) Health Information Technology: Study Design And Scope Factors Associated With Positive Overall Conclusions

There are several caveats. The first has to do with possible selection bias that can be present in any review article.

On article selection for the review:

I should also note that no mention is made of independent reviewers of the article corpus and elimination process. It appears the entire effort was conducted within ONC itself, where a bias towards finding positive results is likely present (and understandable).

Another caveat is the the Health Affairs/ONC article appears to bypass a body of literature, both peer-reviewed and non-peer reviewed, that sheds doubt on health IT in its present form from a number of angles such as I recently aggregated at "An updated reading list on HIT" and at "2009 a pivotal year in healthcare IT." Bypassing literature such as this is a possible major weakness.

Further, in the current political environment, it is not hard to imagine that articles highly critical of health IT, or revealing major mishaps and possibly exposing organizations to litigation, are scarce.

I addressed that in a paper "Remediating an Unintended Consequence of Healthcare IT: A Dearth of Data on Unintended Consequences of Healthcare IT." The paper itself was initially found needing revisions, largely in format, by a small group of blinded reviewers in the Medical Informatics community (with the exception of one faux-newshound who commented that "material like this could be read in any major newspaper", a rather perplexing comment considering the topic). Rather than revise, and not being on the tenure treadmill, I chose instead to publish at the Scribd link above.

The ONC paper does acknowledge this:

They do, however, then issue a value judgment:

I"m not sure a dear relative of mine would find that value judgment heartening. They suffered a crippling injury that would likely not have occurred if paper had been used in the ED rather than an EHR.

I note that if a pharmaceutical company were to issue such a value judgment about a drug as justification for national marketing, they'd likely be nailed to the cross...

The ONC paper also ignores accounts of "near misses" and actual patient injury from impeccable sources, such as in "Health informatics — Guidance on the management of clinical risk relating to the deployment and use of health software. UK National Health Service, DSCN18 (2009), formerly ISO/TR 29322:2008(E)":

They also missed consideration of serious IT defects reports as in the FDA's Maude database that I wrote about at my Jan. 2011 post "MAUDE and HIT Risks."

Another confounding factor is the issue of possible unreliability of the medical literature itself as expressed in a recent post on the IBM Watson supercomputer exuberance:

They do state what I have been writing about for over a decade now:

Dear ONC: see this site, and the many posts since 2004 on this blog.

I was surprised to see this:

As in my post at this link, does this mean that 'anecdotal' accounts of HIT problems will no longer be summarily dismissed? I wonder.

I have also written in the past that in order to truly understand a domain, one must look at both evidence of the upside, and evidence of the downside. My concern is that the latter was not well addressed in this paper. A beneficial technology with a significant downside, especially in medicine, is not ready for national rollout (cf. Vioxx).

In summary, the new ONC paper may present a glimmer of hope that health IT is starting to produce real results. On the other hand, its possible deficiencies and biases might also make it more a political statement than anything else. It will certainly be used as such from the high government perch of HHS regardless. This has already started:

Does the article truly show a breakthrough, or is it a flawed review by a governmental agency that will be used for political purposes? I simply do not know which.

I am certain, however, that there will be active debate and dissection of this paper and its source articles in the months to come by those with more time, resources, and expertise than I have at my disposal.

-- SS

March 10, 2011 addendum:

Trisha Greenhalgh at Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry and the author of the aforementioned comprehensive review article "Tensions and Paradoxes in Electronic Patient Record Research: A Systematic Literature Review Using the Meta-narrative Method" (link to my essay), had this observation about the following passage in the ONC paper:

Prof. Greenhalgh relates: "Given these very fundamental acknowledged biases, I’m very surprised anyone published this paper in its present form.”

-- SS

March 14, 2011 addendum:

Dr. Roy Poses had this to say:

-- SS

It is available at the hyperlink above, but may not be publicly accessible.

The authors all are, or were, ONC officials:

Melinda Beeuwkes Buntin (Melinda.buntin@hhs.gov) is director of the Office of Economic Analysis, Evaluation, and Modeling, Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC), Department of Health and Human Services, in Washington, D.C. Matthew F. Burke is a policy analyst at the ONC. Michael C. Hoaglin is a former policy analyst at the ONC. David Blumenthal is the national coordinator for health information technology.

The abstract is as follows:

ABSTRACT

An unprecedented [indeed- ed.] federal effort is under way to boost [coerce? - ed.] the adoption of electronic health records and spur innovation in health care delivery.We reviewed the recent literature on health information technology to determine its effect on outcomes, including quality, efficiency, and provider satisfaction.We found that 92 percent of the recent articles on health information technology reached conclusions that were positive overall. We also found that the benefits of the technology are beginning to emerge in smaller practices and organizations, as well as in large organizations that were early adopters. However, dissatisfaction with electronic health records among some providers remains a problem and a barrier to achieving the potential of health information technology. [Some? That sounds like an understatement - ed.] These realities highlight the need for studies that document the challenging aspects of implementing health information technology more specifically and how these challenges might be addressed.

I have long stated, at least since 1999, that:

Healthcare information technology (HIT) holds great promise towards improving healthcare quality, safety and costs.

The new ONC review article is certainly pointing in this direction. Perhaps Health Affairs will release it to general circulation.

However, I also wrote:

As we enter the second decade of the 21st century, however, this potential has been largely unrealized. Significant factors impeding HIT achievement have been false assumptions concerning the challenges presented by this still-experimental technology, and underestimations of the expertise essential to achieve the potential benefits of HIT. This often results in clinician-unfriendly HIT design, and HIT leaders and stakeholders operating outside (often far outside) the boundaries of their professional competencies. Until these issues are acknowledged and corrected, HIT efforts will unnecessarily over-utilize precious healthcare resources, will be unlikely to achieve claimed benefits for many years to come, and may actually cause harm.

Whether the new ONC article demonstrates that these issues are starting to approach resolution, or is just another opinion paper not fully supported by facts, is not certain.

Two charts are presented that summarize the findings (click to enlarge):

(Click to enlarge.) Evaluations Of Outcome Measures Of Health Information Technology, By Type And Rating

(Click to enlarge.) Evaluations Of Outcome Measures Of Health Information Technology, By Type And Rating (Click to enlarge.) Health Information Technology: Study Design And Scope Factors Associated With Positive Overall Conclusions

(Click to enlarge.) Health Information Technology: Study Design And Scope Factors Associated With Positive Overall ConclusionsThere are several caveats. The first has to do with possible selection bias that can be present in any review article.

On article selection for the review:

... we decided that to be included in this review, an article had to address a relevant aspect of health IT, as listed in the Appendix [7]; examine the use of health information technology in clinical practice; and measure qualitative or quantitative outcomes. Analyses that forecast the effects of a health IT component were included only if they were based on effects experienced during actual use. ... Using this framework, the review team removed 2,692 articles based on their titles. An additional 1,270 articles were determined to be outside the study’s scope after the team examined the article abstracts. For example, 269 abstracts focused solely on health IT adoption.

[What, exactly, does that mean? Were the problems with HIT adoption potentially significant towards causation of lack of benefit, and/or presence of harm, for instance? - ed]

By the third review stage, the review team had 231 articles. An additional forty-three were excluded after further review because they did not meet the criteria, and thirty-four review articles were dropped from the analyses because they did not present new work.

[What does that mean? Did they drop highly comprehensive articles showing uncertainty in the literature about HIT, such as Greenhalgh's "Tensions and Paradoxes in Electronic Patient Record Research: A Systematic Literature Review Using the Meta-narrative Method" from University College London? That article appeared in the Dec. 2009 Milbank Quarterly. I wrote about it at this link.]

This left 154 studies that met our inclusion criteria, 100 of which were conducted in the United States. This is comparable to the 182 studies found over a slightly longer time period that were evaluated by Goldzweig and colleagues.

I should also note that no mention is made of independent reviewers of the article corpus and elimination process. It appears the entire effort was conducted within ONC itself, where a bias towards finding positive results is likely present (and understandable).

Another caveat is the the Health Affairs/ONC article appears to bypass a body of literature, both peer-reviewed and non-peer reviewed, that sheds doubt on health IT in its present form from a number of angles such as I recently aggregated at "An updated reading list on HIT" and at "2009 a pivotal year in healthcare IT." Bypassing literature such as this is a possible major weakness.

Further, in the current political environment, it is not hard to imagine that articles highly critical of health IT, or revealing major mishaps and possibly exposing organizations to litigation, are scarce.

I addressed that in a paper "Remediating an Unintended Consequence of Healthcare IT: A Dearth of Data on Unintended Consequences of Healthcare IT." The paper itself was initially found needing revisions, largely in format, by a small group of blinded reviewers in the Medical Informatics community (with the exception of one faux-newshound who commented that "material like this could be read in any major newspaper", a rather perplexing comment considering the topic). Rather than revise, and not being on the tenure treadmill, I chose instead to publish at the Scribd link above.

The ONC paper does acknowledge this:

A recent study found that for clinical trials, studies with positive results are roughly four times more likely to be published than those without positive findings. Because the articles were limited to health IT adopters, we anticipated that authors more often approached studies looking for benefits rather than adverse effects.

They do, however, then issue a value judgment:

It is important to note that although publication bias may lead to an underestimation of the trade-offs associated with health IT, the benefits found in the published articles are real.

I"m not sure a dear relative of mine would find that value judgment heartening. They suffered a crippling injury that would likely not have occurred if paper had been used in the ED rather than an EHR.

I note that if a pharmaceutical company were to issue such a value judgment about a drug as justification for national marketing, they'd likely be nailed to the cross...

The ONC paper also ignores accounts of "near misses" and actual patient injury from impeccable sources, such as in "Health informatics — Guidance on the management of clinical risk relating to the deployment and use of health software. UK National Health Service, DSCN18 (2009), formerly ISO/TR 29322:2008(E)":

Annex A

Examples of potential harm presented by health software

GP prescribing decision support

In 2004 the four most commonly used primary care systems were subjected to eighteen, potentially serious, realistic scenarios including an aspirin prescription for an eight year old, penicillin for a patient with penicillin allergy and a combined oral contraceptive for a patient with a history of deep vein thrombosis. Using dummy records, all eighteen scenarios failed to produce appropriate alerts by all of the systems, most of the time. The best score was a system that flagged up seven appropriate alerts. The health organization clearly has, in such a system deployment, a key responsibility to ensure that knowledge bases used within a design are correctly populated and aligned with clinical practice within their organization.

Inadvertent accidental prescribing of dangerous drugs (such as methotrexate)

This incident occurred when a user of a primary care system attempted to issue two repeat items. The items were highlighted and instead of the issue selected repeats button, the prescribe acute issues from the formulary button was pressed. This brought up the formulary dialogue which contained the high risk items. Either the issue button was then pressed or the particular items were double clicked. When the warning messages came up, they were all ignored and proceed and issue selected. The user chose the first item presented on the formulary list, which just so happened to be a methotrexate injection. In this particular case, it was determined that patient risk was minimal as the treatment was rarely used in primary care and would, in practice, be rejected by the pharmacist. To preclude any recurrence of the problem, access to the high risk formulary was removed from the formulary part of the acute drug issue dialogue. This example again demonstrates the need to align clinical practice and authority levels with the knowledge and rule bases within the system. Wherever possible, design and implementation of health software systems should be undertaken to improve control and accuracy, note introduce new exposures. Furthermore the hazard and risk assessment of this situation may well not apply in other settings, e.g. prescription issue by nursing staff on a ward versus a pharmacist in a retail store.

Incorrect patient details retrieved from radiology information system

This incident arose from the fact that medical reference numbers (MRNs) are usually prefixed by an alpha code. Some hospitals however do not use these prefixes and identical MRNs can be generated. This gave rise to the creation of shared MRNs and subsequent confusion of records in the central datastore when retrieval key is the Medical Record Number. Four specific instances were found where a patient number had been entered in the radiology information system and incorrect patient details had been retrieved. The manufacturer could have built in an appropriate format check during development. Alternatively, the problem could have been spotted by the health organization if a structured risk assessment had been undertaken.

Drug mapping error

Sodium valproate 200 mg slow release was incorrectly mapped to sodium valproate 200 mg in a formulary encoded into a health software system. These are anti-epilepsy drugs and thus the implications for patient safety could be significant. This particular incident is just one of many that have been reported in relation to drug mapping.

An initial investigation indicated that 35 prescriptions had been generated using the incorrect map. Corrective action included contacting the relevant primary care practices to check upon patient health and the supplier to correct the mapping process to ensure no further incorrect prescriptions were generated. As before, this was a design/coding error by the manufacturer but was compounded by the health organization not checking the mappings and failing either to build in appropriate prescribing controls, or map the controls to health organization individuals with the appropriate experience and authority.

Pre-natal screening

The ages of women who had undergone pre-natal screening were wrongly computed by a health software system. As a result 150 women were wrongly notified that they were at no risk. Of these, four gave birth to Down's syndrome babies and two others made belated decisions to have abortions.

Patient identification

A student died of meningitis because of a misspelling of her name and inadequacy in computer use. The student was admitted and a blood test proved negative for meningitis. The following day another blood test was taken and filed on a new computer entry but the letter ―p was missed in the spelling of the name. When a doctor looked up results they were presented with only the first negative tests result because of the misspelling. If the second result had been seen it would have triggered further investigations and probable diagnosis of meningitis. The investigating panel concluded that problems with the health software system had been greater than first thought and in this case there was a combination of a misspelled name and the doctor not being able to use the computer system property. The health software system could have been designed to use unique numbers either instead of the name or in addition to it.

They also missed consideration of serious IT defects reports as in the FDA's Maude database that I wrote about at my Jan. 2011 post "MAUDE and HIT Risks."

Another confounding factor is the issue of possible unreliability of the medical literature itself as expressed in a recent post on the IBM Watson supercomputer exuberance:

Consider the issue of the medical literature suffering from numerous conflict of interest and dishonesty-related phenomema making it increasingly untrustworthy, as pointed out by Roy Poses in a Dec. 2010 post "The Lancet Emphasizes the Threats to the Academic Medical Mission", at my Aug. 2009 post "Has Ghostwriting Infected The "Experts" With Tainted Knowledge, Creating Vectors for Further Spread and Mutation of the Scientific Knowledge Base?" and elsewhere on this blog.

They do state what I have been writing about for over a decade now:

... In fact, the stronger finding may be that the “human element” is critical to health IT implementation. The association between the assessment of provider satisfaction and negative findings is a strong one. This highlights the importance of strong leadership and staff “buy-in” [which will only occur if the systems are not miserable examples of poor engineering, not due to P.R. or the irrational exuberance of others - ed.] if systems are to successfully manage and see benefit from health information technology. The negative findings also highlight the need for studies that document the challenging aspects of implementing health IT more specifically and how these challenges might be addressed.

Dear ONC: see this site, and the many posts since 2004 on this blog.

I was surprised to see this:

... Taking a cue from the literature on continuous quality improvement, every negative finding can be a treasure if it yields information on how to improve implementation strategies and design better health information technologies.

As in my post at this link, does this mean that 'anecdotal' accounts of HIT problems will no longer be summarily dismissed? I wonder.

I have also written in the past that in order to truly understand a domain, one must look at both evidence of the upside, and evidence of the downside. My concern is that the latter was not well addressed in this paper. A beneficial technology with a significant downside, especially in medicine, is not ready for national rollout (cf. Vioxx).

In summary, the new ONC paper may present a glimmer of hope that health IT is starting to produce real results. On the other hand, its possible deficiencies and biases might also make it more a political statement than anything else. It will certainly be used as such from the high government perch of HHS regardless. This has already started:

... President Obama and Congress envisioned that the HITECH Act would provide benefits in the form of lower costs, better quality of care, and improved patient outcomes. This review of the recent literature on the effects of health information technology is reassuring: It indicates that the expansion of health IT in the health care system is worthwhile.

[Note the use of "is worthwhile" as opposed to "may be worthwhile", a continuation of the "it's proven, nothing else to say" style I noted at my July 2010 post "Science or Politics? The New England Journal and "The 'Meaningful Use' Regulation for Electronic Health Records." Such statements of absolute certainty are of concern; they remind me of the global warming debate - ed.]

...Thus, with HITECH, providers have an unparalleled opportunity to accelerate their adoption of health information technology and realize benefits for their practices, institutions, patients, and the broader system. [Ditto - ed.]

Does the article truly show a breakthrough, or is it a flawed review by a governmental agency that will be used for political purposes? I simply do not know which.

I am certain, however, that there will be active debate and dissection of this paper and its source articles in the months to come by those with more time, resources, and expertise than I have at my disposal.

-- SS

March 10, 2011 addendum:

Trisha Greenhalgh at Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry and the author of the aforementioned comprehensive review article "Tensions and Paradoxes in Electronic Patient Record Research: A Systematic Literature Review Using the Meta-narrative Method" (link to my essay), had this observation about the following passage in the ONC paper:

“Our findings must be qualified by two important limitations: the question of publication bias, and the fact that we implicitly gave equal weight to all studies regardless of study design or sample size.”

Prof. Greenhalgh relates: "Given these very fundamental acknowledged biases, I’m very surprised anyone published this paper in its present form.”

-- SS

March 14, 2011 addendum:

Dr. Roy Poses had this to say:

Dr Silverstein commented on a new review of research of health care information technology whose results were mainly optimistic. The authors were from the US government agency that promotes health care IT, so its optimism is not surprising. However, its credibility was unclear, since it did not appear to be systematic. [In general, one at least assesses and takes into account the methodologic quality of studies used in a systematic review, and does not "give equal weight to all studies regardless of study design or sample size" - ed.]

Furthermore, the authors had no methodologic standards whatsoever for article inclusion. [They did, sort of, as in my paragraphs "On article selection for the review:", but one might term the standards "loose" - ed.] The review included qualitative studies that were probably not meant to be evaluative, and observational studies subject to severe methodologic bias.

The publication of this review demonstrated how the conventional wisdom is continually reinforced based on the strength of the influence of its proponents, rather than the strength of the supporting evidence. Adaptation of new drugs and devices should be based on evidence that their benefits outweigh their harms, rather than the enthusiasm and financial interests of their proponents.

-- SS

"Cogs in the Corporate Machine" - More on the Plight of Corporate Physicians

We discussed last week some of the perils of the latest trend towards the corporatization of medicine, practicing physicians becoming employees of hospital systems, including for-profit corporate systems. A recent article in Medscape Business of Medicine included a striking anecdote about the life of a corporate physician.

Controlling Referrals by Contractual Provision

It started with the revelation that some employed physicians may sign contracts that obligate them to refer patients within the corporate system, even if that is not in their best interests:

It also included the observation that corporate physicians may be abruptly laid off. Worse, being laid off means having to leave town, because apparently even laid-off physicians are still obligated by non-compete clauses in their contracts:

The article's introduction emphasized the problem of physicians signing onerous contracts, perhaps without fully understanding them or without getting adequate legal advice:

The introduction ended ominously:

Oddly enough, after that striking beginning, the article peters off into a discussion of some "gripes of employed physicians," which either soft-pedaled or failed to include the issues listed above.

The specific issues, and the general response of physicians to their role as corporate wage slaves deserve further consideration.

Signing Bad Contracts

First, the notion that physicians frequently sign contracts, particularly such important contracts as their own employment agreements, without reading them, without clearly understanding them, and without obtaining competent legal counsel is very disturbing. A physician who signs a contract without reading it, understanding it, and getting competent legal advice about it is at best naive to the point of foolishness.

My late father, an attorney, done told me to "never sign a contract you haven't read and understood." Contracts are - surprise - enforceable legal documents that may involve surrendering important rights. One should never sign a contract without being satisfied that its benefits outweigh its harms.

It could be that physicians who so blithely sign contracts are exhibiting learned helplessness. Maybe they feel somehow pressured to apparently voluntarily agree to doing something that ultimately will harm them. I am not sure that simply declaring on a blog that we will have to unlearn our helplessness if we are ever to save medicine and health care will do much to solve what may be a fairly deep problem. But we must do so.

In addition, contracts are valid if entered into voluntarily. It may be that some physicians truly sign contracts under duress. Those contracts may not be valid, and could be challenged if they were so signed (again, if physicians are willing to unlearn their helplessness enough to get the counsel of a competent attorney.)

Stopping "Leakage" Possibly Unethically, Maybe Illegally?

The physician in the example above apparently had a contract provision which was violated simply by referring patients to competing facilities. This appears to be an extreme way for a hospital to deal with the problem of "leakage," that is, the financial problem to the hospital caused when patients are referred outside the system. Note that we discussed (here and here) the example of a for-profit hospital system with a large number of physician employees pushed to choke off "leakage" of patient referrals outside the system.

Although leakage may pose financial problems for hospitals, fighting leakage may lead to ethical problems. Physicians are supposed to decide how to manage patients, and specifically to decide where to refer patients in the patients' interests, not just to keep money flowing to the health care system. "Leakage reduction" may possibly threaten physicians' first commandment, to make decisions to maximize benefits and minimize harms to individual patients, before all other considerations.

Worse, in the example cited in the Medscape paper, the leakage reduction was apparently implemented not by just trying to persuade doctors to keep patients within the system, but by a contract provision that somehow forbade referrals out of the system. That may have not only been unethical, but it could have been illegal.

The "Stark Law" (Title 42, Chapter 7, Subchapter XVIII, Part E, Section 1395 of the US Code) generally prohibits basing referral decisions on payments. Full-time employed physicians are exempt from some of its provisions, but only if the physicians' "amount of remuneration under employment" "is not determined in a manner that takes into account (directly or indirectly) the volume or value of any referrals by the referring physician." Therefore, were the contract referred to above to have forbidden outside referrals on pain of termination or reduction in remuneration, it could potentially violate this law.

There have been rumors that physicians have been pushed to sign contracts that could so violate the Stark Law, but the published example above makes this a real possibility.

Physicians ought not to sign contracts that seem to limit referrals under penalty of pay reduction or termination, which may be both unethical and illegal. Any physician presented with or who has signed such a contract ought to consult a competent attorney.

If hospitals and hospital systems are trying to force physicians to make referrals based on the hospitals' financial advantage instead of in the best interests of patients, that is reprehensible. If these organizations are trying to do so via contractual provisions, this deserves investigation, including investigation by the relevant law enforcement agencies.

Don't Be a Corporate Cog

This article underscores my previously expressed fears about how making physicians into corporate employees may remove the last barriers preventing patients from becoming corporate financial cannon fodder. Physicians' most central professional value is to put patients' interests first. Practicing physicians who practice as corporate employees are at risk of being pressured, or even threatened under the cover of contract enforcement to put their corporate employers' revenues ahead of patients' interests.

Physicians should not let their patients, and their own values be so threatened. Physicians who have inadvertently, foolishly, or under duress signed contracts that could threaten their professionalism and their patients' welfare need to do the right thing and challenge these contracts, or else there will soon be nothing left of the medical profession, and no one left to ethically care for patients.

Controlling Referrals by Contractual Provision

It started with the revelation that some employed physicians may sign contracts that obligate them to refer patients within the corporate system, even if that is not in their best interests:

Victoria Rentel, a family physician in Columbus, Ohio, joined a hospital-owned group several years ago. At first, nearly everything went fine. There were a few glitches: she'd occasionally order tests or consults at competing facilities, either for patient convenience or because of health plan coverage. When the hospital's administrators found out, they told her it was a violation of her contract; but that didn't stop her because she knew the hospital never enforced this provision.A Non-Compete Clause, Even for a Laid-Off Physician

It also included the observation that corporate physicians may be abruptly laid off. Worse, being laid off means having to leave town, because apparently even laid-off physicians are still obligated by non-compete clauses in their contracts:

Then, out of the blue, she was informed that the hospital was going to close her practice within 45 days. She knew this wasn't her fault; the recession had hit the hospital hard, and it was laying off nearly half of the primary care doctors in her group. Still, it was a hard pill to swallow.Signing Contracts Without Understanding Them

Making matters worse, her contract's noncompete clause prohibited her from going to work for any of the other healthcare systems in town. To avoid legal sanctions, she joined the student health service at Ohio State University.

The article's introduction emphasized the problem of physicians signing onerous contracts, perhaps without fully understanding them or without getting adequate legal advice:

Many other physicians -- especially those who, like Rentel, were previously in private practice -- complain about their jobs. In some cases, it's because physicians rushed into the arms of a hospital without looking carefully at their contracts or asking the right questions during their job interviews.Cogs in the Corporate Machine

The introduction ended ominously:

Ultimately, the loss of control over their own professional lives is what irks employed doctors the most if they used to be in private practice. But some doctors also get the sinking feeling that they've become cogs in the corporate machine.

'The reality is that when you work for a hospital system, you're a service line,' says Rentel. 'And because primary care reimbursement is relatively low, you're a service line that feeds more lucrative service lines.'

Oddly enough, after that striking beginning, the article peters off into a discussion of some "gripes of employed physicians," which either soft-pedaled or failed to include the issues listed above.

The specific issues, and the general response of physicians to their role as corporate wage slaves deserve further consideration.

Signing Bad Contracts

First, the notion that physicians frequently sign contracts, particularly such important contracts as their own employment agreements, without reading them, without clearly understanding them, and without obtaining competent legal counsel is very disturbing. A physician who signs a contract without reading it, understanding it, and getting competent legal advice about it is at best naive to the point of foolishness.

My late father, an attorney, done told me to "never sign a contract you haven't read and understood." Contracts are - surprise - enforceable legal documents that may involve surrendering important rights. One should never sign a contract without being satisfied that its benefits outweigh its harms.

It could be that physicians who so blithely sign contracts are exhibiting learned helplessness. Maybe they feel somehow pressured to apparently voluntarily agree to doing something that ultimately will harm them. I am not sure that simply declaring on a blog that we will have to unlearn our helplessness if we are ever to save medicine and health care will do much to solve what may be a fairly deep problem. But we must do so.

In addition, contracts are valid if entered into voluntarily. It may be that some physicians truly sign contracts under duress. Those contracts may not be valid, and could be challenged if they were so signed (again, if physicians are willing to unlearn their helplessness enough to get the counsel of a competent attorney.)

Stopping "Leakage" Possibly Unethically, Maybe Illegally?

The physician in the example above apparently had a contract provision which was violated simply by referring patients to competing facilities. This appears to be an extreme way for a hospital to deal with the problem of "leakage," that is, the financial problem to the hospital caused when patients are referred outside the system. Note that we discussed (here and here) the example of a for-profit hospital system with a large number of physician employees pushed to choke off "leakage" of patient referrals outside the system.

Although leakage may pose financial problems for hospitals, fighting leakage may lead to ethical problems. Physicians are supposed to decide how to manage patients, and specifically to decide where to refer patients in the patients' interests, not just to keep money flowing to the health care system. "Leakage reduction" may possibly threaten physicians' first commandment, to make decisions to maximize benefits and minimize harms to individual patients, before all other considerations.

Worse, in the example cited in the Medscape paper, the leakage reduction was apparently implemented not by just trying to persuade doctors to keep patients within the system, but by a contract provision that somehow forbade referrals out of the system. That may have not only been unethical, but it could have been illegal.

The "Stark Law" (Title 42, Chapter 7, Subchapter XVIII, Part E, Section 1395 of the US Code) generally prohibits basing referral decisions on payments. Full-time employed physicians are exempt from some of its provisions, but only if the physicians' "amount of remuneration under employment" "is not determined in a manner that takes into account (directly or indirectly) the volume or value of any referrals by the referring physician." Therefore, were the contract referred to above to have forbidden outside referrals on pain of termination or reduction in remuneration, it could potentially violate this law.

There have been rumors that physicians have been pushed to sign contracts that could so violate the Stark Law, but the published example above makes this a real possibility.

Physicians ought not to sign contracts that seem to limit referrals under penalty of pay reduction or termination, which may be both unethical and illegal. Any physician presented with or who has signed such a contract ought to consult a competent attorney.

If hospitals and hospital systems are trying to force physicians to make referrals based on the hospitals' financial advantage instead of in the best interests of patients, that is reprehensible. If these organizations are trying to do so via contractual provisions, this deserves investigation, including investigation by the relevant law enforcement agencies.

Don't Be a Corporate Cog

This article underscores my previously expressed fears about how making physicians into corporate employees may remove the last barriers preventing patients from becoming corporate financial cannon fodder. Physicians' most central professional value is to put patients' interests first. Practicing physicians who practice as corporate employees are at risk of being pressured, or even threatened under the cover of contract enforcement to put their corporate employers' revenues ahead of patients' interests.

Physicians should not let their patients, and their own values be so threatened. Physicians who have inadvertently, foolishly, or under duress signed contracts that could threaten their professionalism and their patients' welfare need to do the right thing and challenge these contracts, or else there will soon be nothing left of the medical profession, and no one left to ethically care for patients.

Tuesday, March 8, 2011

Those Big Doors Keep Revolving

A few months ago, we discussed the revolving door that seems to connect US government leadership positions and leadership positions of commercial health care firms. There are other such revolving doors, like two recently discovered just north of here.

State Government to For-Profit Hospitals

As reported by the Boston Herald:

Furthermore,

Note that we have previously discussed the Steward Health Care System, the new name given to the Caritas Christi system after it was bought out by private equity firm Cerberus Capital Management. Steward's aggressive plan to stamp out "leakage" raised concerns that the new movement to make practicing physicians employees could push them to do what is best for the company's bottom line rather than for patients.

We previously suggested that deals that turn previously non-profit health systems and physicians' practices into for-profit corporations deserve considerable scrutiny. After Caritas became Steward, state government officials promised close oversight. Now Steward has acquired a new executive who has friends in state government.

Non-Profit Health Insurance/ Managed Care by Way of a Political Campaign to Health Care Venture Capital

This story also came from the Boston Herald:

In addition,

Note that managed care was originally touted as a way to control health care costs, and that the commercial health care insurance companies/ managed care organizations claim to be doing all they can to control costs. Such a focus on cost control would imply that they ought to be able to vigorously negotiate at arms' length with health care providers and drug and device companies. Now some device companies have acquired a new venture capital overseer who has friends in insurance and managed care.

Summary

Not only are there revolving doors connecting the national government and large commercial health firms, but also connecting state government and regional hospital systems, and non-profit health care insurers/ managed care organizations and device companies.

This is just some more evidence that people in the leadership of large health care organizations have more in common with each other, even if their organizations are supposed to be competing or negotiating at arms length, than they have with patients, clients, customers and the public at large.

The various revolving doors appear not to align the interests of leaders of health care organizations with their organizations' stated missions, or with promoting the health of patients. To truly reform health care, we need to expose these doors to more sunlight, and then think about retarding their spin or even locking them in place.

State Government to For-Profit Hospitals

As reported by the Boston Herald:

David Morales, a longtime trusted adviser to [Massachusetts] Gov. Deval Patrick, became the latest official to leave the administration as he stepped down from a top health-care post for a private sector gig.

Morales resigned abruptly yesterday to take a position with Steward Health Care System.

Furthermore,

Morales worked as a top adviser during the governor’s first term before taking a $128,000-a-year post in 2009 as commissioner of the Division of Health Care Finance and Policy. His resignation was effective yesterday.

Note that we have previously discussed the Steward Health Care System, the new name given to the Caritas Christi system after it was bought out by private equity firm Cerberus Capital Management. Steward's aggressive plan to stamp out "leakage" raised concerns that the new movement to make practicing physicians employees could push them to do what is best for the company's bottom line rather than for patients.

We previously suggested that deals that turn previously non-profit health systems and physicians' practices into for-profit corporations deserve considerable scrutiny. After Caritas became Steward, state government officials promised close oversight. Now Steward has acquired a new executive who has friends in state government.

Non-Profit Health Insurance/ Managed Care by Way of a Political Campaign to Health Care Venture Capital

This story also came from the Boston Herald:

Four months after his failed Massachusetts gubernatorial bid, Charlie Baker has landed a private-sector job at a Cambridge venture capital firm.

The former Harvard Pilgrim Health Care CEO is now an 'executive in residence' for General Catalyst Partners. He’ll focus on working with small and midsize health-care services companies for the VC firm, which has $1.7 billion under management across five funds.

In addition,

Health-related companies already in General Catalyst’s portfolio include iWalk, a Cambridge developer of orthotic and prosthetic devices, and North Carolina-based TearScience, which specializes in diagnostic and treatment devices for evaporative dry eye in addition to several still in stealth mode.

Note that managed care was originally touted as a way to control health care costs, and that the commercial health care insurance companies/ managed care organizations claim to be doing all they can to control costs. Such a focus on cost control would imply that they ought to be able to vigorously negotiate at arms' length with health care providers and drug and device companies. Now some device companies have acquired a new venture capital overseer who has friends in insurance and managed care.

Summary

Not only are there revolving doors connecting the national government and large commercial health firms, but also connecting state government and regional hospital systems, and non-profit health care insurers/ managed care organizations and device companies.

This is just some more evidence that people in the leadership of large health care organizations have more in common with each other, even if their organizations are supposed to be competing or negotiating at arms length, than they have with patients, clients, customers and the public at large.

The various revolving doors appear not to align the interests of leaders of health care organizations with their organizations' stated missions, or with promoting the health of patients. To truly reform health care, we need to expose these doors to more sunlight, and then think about retarding their spin or even locking them in place.

The Future Pathways for e-Health in NSW

Prof. Patrick has now added a new section to his report on health IT in NSW Australia, entitled "The Future Pathways for e-Health in NSW." It is available at this link (PDF).

It inoculates against most of the 'Ten Plagues' that bedevil health IT projects (such as the IT-clinical leadership inversion, lack of transparency, suppression of defects reporting, magical thinking about the technology, and lack of accountability of the bureaucrats).

Emphases mine:

I can only add that our own ONC office (Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT of the Dept. of HHS) had more granular recommendations about expertise levels required for leadership roles in such undertakings. I wrote about them at my Dec. 2009 post "ONC Defines a Taxonomy of Robust Healthcare IT Leadership."

--SS

It inoculates against most of the 'Ten Plagues' that bedevil health IT projects (such as the IT-clinical leadership inversion, lack of transparency, suppression of defects reporting, magical thinking about the technology, and lack of accountability of the bureaucrats).

Emphases mine:

In Short Term ( 0-3 months)The de facto "National Program for IT in the HHS" here in the United States needs a similar inoculation.

1. Halt further rollouts of Firstnet or other CIS systems. The current roll-out programs use significant efforts in training staff for a system that is counterproductive to patient well being.

2. Complete a full and thorough risk assessment analysis and usability of the software. The CIS report indicates there are a number of risks in the current software that are not likely to have been assessed in the past.

3. Address the current problems before doing anything else. There are a number of problems that appear solvable in the short term that would improve the situation for current users, such as providing needed reports.

4. Create the NSW IT Improvement Panel composed of ED Directors, IT-savvy clinical and quality improvement staff responsible for advising on the preparedness and process of the rollout.

5. Create an effective error and bug reporting mechanism that is viewable by all ED directors and with the display of the priority of each entry and expected completion time.

6. Initiate a high profile campaign to encourage staff to lodge fault records on anything they discover wrong, problematic or inefficient in using the system.

In the longer term (3-12 months)

1. Review the Health Support Services and make it clinically accountable by appointing a clinical head with an IT education.

2. Create a culture change in the HSS. The current operation of the HSS seems to be devoid of influence from the clinical community.

3. All NSW CIS system procurement should be guided by an IT Advisory Board of IT experienced clinical, academic and medical software industry experts.

4. Create pathways for hospitals that wish to be early adopters and take a lead role in the development of new methods for using and deploying IT systems.

5. Support innovation within the Australian medical software communities that contribute to a culture of innovation and continuous quality improvement.

6. Adopt transparency rules in all new healthcare information acquisitions. Secrecy has bedevilled the efforts of staff and management to get improvements in the CIS systems and hold service agents accountable for their failure to comply to service level agreements. All agreements about a signed contract should be available to the ED Directors.

7. Replace the State Based Build policy with a policy of providing a technology to match the technology experience of the individual departments so that leaders are not dragged backwards with inappropriate technology installation

I can only add that our own ONC office (Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT of the Dept. of HHS) had more granular recommendations about expertise levels required for leadership roles in such undertakings. I wrote about them at my Dec. 2009 post "ONC Defines a Taxonomy of Robust Healthcare IT Leadership."

--SS

Monday, March 7, 2011

Are Those Sockpuppers From Down Under?

We at Healthcare Renewal have had experience with the healthcare sock puppets. They are shills, a person or group working on behalf of a company or other special interest. They attempt to use distraction, ad hominem, misdirection and other psyops tactics to attack points of view they don't like. They also plant memes they or their sponsor deem desirable.

They are universally anonymous in their postings.

One got careless and got nailed via IP forensics, as at my Jan. 2010 post "More on Perversity in the Healthcare IT World: Is Meditech Employing Sockpuppets?" and my semi-satirical followup post a few days later, "Socky the Meditech Sockpuppet on Vacation?" after he/she disappeared after exposure.

A Healthcare Renewal reader with an MBA at that time non-anonymously related the following (emphases mine):

It seems this foul type of creature is starting to crawl out of the woodwork regarding Prof. Jon Patricks' analysis of an ED EHR system mandated by the state's government of NSW for public hospitals, as I wrote about in my posts such as on Mar. 5, 2011 at "On an EMR Forensic Evaluation by Professor Jon Patrick from Down Under: More Thoughts.".

They may be corporate, they may be government. They likely have a financial stake in the ED EHR project as well.

For instance, the sockpuppet/shill comments are starting to appear at the Australian Health Information Technology blog of Dr David More MB, PhD, FACHI at http://aushealthit.blogspot.com:

(Sounds like a kindred mission relative to HC Renewal.)

For instance at Dr. More's post "Prof Patrick Has Really Hit the Bullseye It Would Seem. Lots of Supportive Comments From All Over!" we see the following sock puppet-like comments rearing their holey (not holy) woven head:

and the ever-so-common refrain of:

Ink is never put to specifics of the supposed transgressions in these largely ad hominem, anonymous attacks.

If those who wrote them had the fortitude to identify themselves, perhaps they might be somewhat credible. However that rarely if ever is the case.

In my humble opinion, such comments are risible, not even worth the electrons they're written with.

Except for amusement:

p.s. an ED EHR-injured relative of mine has a message to the sockpuppets of the world. It's not fit for a public site, but it has to do with travel to a very hot, deep, sulfurous place in the earth.

-- SS

They are universally anonymous in their postings.

One got careless and got nailed via IP forensics, as at my Jan. 2010 post "More on Perversity in the Healthcare IT World: Is Meditech Employing Sockpuppets?" and my semi-satirical followup post a few days later, "Socky the Meditech Sockpuppet on Vacation?" after he/she disappeared after exposure.

A Healthcare Renewal reader with an MBA at that time non-anonymously related the following (emphases mine):

In reading this thread of comments I have to believe IT Guy [the Sock puppet - ed.] is a salesperson. My only question is: Were you assigned this blog or did you choose it? We had this problem a number of years ago where a salesperson was assigned a number of blogs with the intent of using up valuable time in trying to discredit the postings.

In my very first sales class we learned to focus on irrelevant points, constantly shift the discussion, and generally try to distract criticism. I would say that HCR is creating heat for IT Guy’s employer and the industry in general.

I find it sad that a company would allow an employee to attack anyone in an open forum. IT Guy needs to check with his superiors to find out if they approve of this use of his time, and I hope he is not using a company computer, unless once again this attack is company sanctioned.

Steve Lucas

It seems this foul type of creature is starting to crawl out of the woodwork regarding Prof. Jon Patricks' analysis of an ED EHR system mandated by the state's government of NSW for public hospitals, as I wrote about in my posts such as on Mar. 5, 2011 at "On an EMR Forensic Evaluation by Professor Jon Patrick from Down Under: More Thoughts.".

They may be corporate, they may be government. They likely have a financial stake in the ED EHR project as well.

For instance, the sockpuppet/shill comments are starting to appear at the Australian Health Information Technology blog of Dr David More MB, PhD, FACHI at http://aushealthit.blogspot.com:

This blog has only three major objectives.

The first is to inform readers of news and happenings in the e-Health domain, both here in Australia and world-wide.

The second is to provide commentary on what seems to have become the lamentable state of e-Health in Australia and to foster improvement.

The third, sadly, is now to try and force accountability for the actions of, and the funds spent, by NEHTA. [National E-Health Transition Authority as at this link - ed.]

(Sounds like a kindred mission relative to HC Renewal.)

For instance at Dr. More's post "Prof Patrick Has Really Hit the Bullseye It Would Seem. Lots of Supportive Comments From All Over!" we see the following sock puppet-like comments rearing their holey (not holy) woven head:

... It seems that the heuristic axiom of Ockham’s Razor (as presented by Jon) is the design criteria by which Jon thinks NSW Health should have selected their CIS ... unbelievable!and

Unfortunately Jon has not proposed any practical alternatives in his papers. His papers are full of opinions, unfounded claims and incorrect facts (not to mention the countless flaws in his research methodologies).

Dr Patrick - you are so misinformed. There are so many untruths in what you report. Why is this? Because you interviewed 7 people. Being Directors, what is the likelihood they are hands on with the system? Minimal I would say from experience in the EDs. Call yourself a researcher - huh! It is a totally biased report which reflects the opinions of those with an axe to grind. Why don't you talk to some nurses,clerical staff and junior doctors? There are hundreds of them working in EDs across the state. Their opinion should matter as they are the ones caring for our patients. You should be ashamed of yourself! I certainly would not hire you to do a research project if this is the biased and blatantly incorrect rubbish that you come up with. Shame on you!!

and the ever-so-common refrain of:

Has Dr Patrick ever completed (or even been involved in) an implementation of an EMR (at all or of any scale)? Can someone tell us what makes him an authority the subject? [I, OTOH, have done so, authoring, implementing, managing for hospitals and major pharma - ed.]

... His view is unbalanced and his paper is clearly bias. How Sydney University tolerates papers of such poor quality and biasness (being published by their professors) is beyond me. [Paper is 'clearly bias'? Biasness? This person needs a grammar lesson - ed.]

Ink is never put to specifics of the supposed transgressions in these largely ad hominem, anonymous attacks.

If those who wrote them had the fortitude to identify themselves, perhaps they might be somewhat credible. However that rarely if ever is the case.

In my humble opinion, such comments are risible, not even worth the electrons they're written with.

Except for amusement:

p.s. an ED EHR-injured relative of mine has a message to the sockpuppets of the world. It's not fit for a public site, but it has to do with travel to a very hot, deep, sulfurous place in the earth.

-- SS

EHR ED's in New South Wales. Will the Problems Magically "Disappear?"

It occurs that one could look at Prof. Jon Patrick's recent health IT forensic analysis as a kind of "indictment" of the industry.

He can be seen as suggesting the industry needs to be "put on trial" (figuratively) regarding "crimes" (again, figuratively speaking) they've committed with regard to IT robustness and reliability. The latter translate directly to patient safety.

In a lawsuit such as a medical malpractice trial, obvious as well as potential evidence is put under "legal hold." For instance, if an EHR defect is suspected, metadata, audit trails, and patient data are asked (or should be asked) to be frozen or archived in the state they were in at the time of the alleged accident.

It can take a page or three (or more) of specifications simply to define what information, exactly, needs to be put on legal hold. My former staff were frequently required to place myriad materials on legal hold at Merck Research Labs, for example, baed on the lawsuit du jour.

Once frozen, discovery and forensic analysis of these now-static data can then proceed. In fact, cases can be lost on the basis of evidence of an archiving omissions, destruction or tampering when information holds are requested.

It occurs to me that Prof. Patrick has given the industry a detailed look into factors they could start to remediate, without publicity and without telling anyone. While this would be a net plus for patients, it might result in less of a learning experience to the industy than that industry needs, to motivate the industry to avoid future product engineering and quality issues and put quality (not simply margin) as priority #1.

I therefore would believe a "hold" put on the present state of these ED EMR systems, or a "snapshot" of their current state (i.e., an evaluation environment mirrored from the present operational one) would allow a careful evaluation of the impact of the issues noted in the study.

Such an evaluation would be far more difficult with a cybernetic moving target.

The "snapshot" idea would allow evaluation of system risk levels, intermittent "glitches", interference with workflows, etc. in a controlled testing environment, using mock data or data drawn from actual cases.

The "snapshot" approach would also allow incremental remediation of the "live" system that comes out of safe, controlled testing, rather than sticking with what exists now until the studies could be completed on the as-is system, and then applying all the fixes as one or more large "upgrades."

I, for one, would be interested in studying this "built by software professionals" system and comparing it to health IT systems we "academic nerds" were authoring, say, 10-15 years ago.

-- SS

He can be seen as suggesting the industry needs to be "put on trial" (figuratively) regarding "crimes" (again, figuratively speaking) they've committed with regard to IT robustness and reliability. The latter translate directly to patient safety.

In a lawsuit such as a medical malpractice trial, obvious as well as potential evidence is put under "legal hold." For instance, if an EHR defect is suspected, metadata, audit trails, and patient data are asked (or should be asked) to be frozen or archived in the state they were in at the time of the alleged accident.

It can take a page or three (or more) of specifications simply to define what information, exactly, needs to be put on legal hold. My former staff were frequently required to place myriad materials on legal hold at Merck Research Labs, for example, baed on the lawsuit du jour.

Once frozen, discovery and forensic analysis of these now-static data can then proceed. In fact, cases can be lost on the basis of evidence of an archiving omissions, destruction or tampering when information holds are requested.

It occurs to me that Prof. Patrick has given the industry a detailed look into factors they could start to remediate, without publicity and without telling anyone. While this would be a net plus for patients, it might result in less of a learning experience to the industy than that industry needs, to motivate the industry to avoid future product engineering and quality issues and put quality (not simply margin) as priority #1.

I therefore would believe a "hold" put on the present state of these ED EMR systems, or a "snapshot" of their current state (i.e., an evaluation environment mirrored from the present operational one) would allow a careful evaluation of the impact of the issues noted in the study.

Such an evaluation would be far more difficult with a cybernetic moving target.

The "snapshot" idea would allow evaluation of system risk levels, intermittent "glitches", interference with workflows, etc. in a controlled testing environment, using mock data or data drawn from actual cases.

The "snapshot" approach would also allow incremental remediation of the "live" system that comes out of safe, controlled testing, rather than sticking with what exists now until the studies could be completed on the as-is system, and then applying all the fixes as one or more large "upgrades."

I, for one, would be interested in studying this "built by software professionals" system and comparing it to health IT systems we "academic nerds" were authoring, say, 10-15 years ago.

-- SS

Getting Out of Our RUC - "An Open Letter To Primary Care Physicians"

Since 2007, we have been writing about the secretive RUC (RBRVS Update Committee), the private AMA committee that somehow has managed to get effective control over how Medicare pays physicians. The RUC has been accused of setting up incentives that strongly favor invasive, high technology procedures while disfavoring primary care and other "cognitive medicine." Despite the central role of (perverse) incentives in raising health care costs while limiting access and degrading quality, there has been surprisingly little discussion about the pivotal role played by the RUC.

Now there is a movement afoot to replace the RUC. In a new post on the Care and Cost blog, and the Replace the RUC site, Paul M. Fischer and Brian Klepper urged four approaches:

1. Make the public aware of the RUC’s role and urge the primary care societies to stop “enabling” the RUC through their participation.

2. Recruit experts who can credibly calculate the economic impacts of the RUC’s actions, and who can devise alternative payment methodologies.

3. Demonstrate the unlawfulness of CMS’ (and HCFA’s) two-decades long reliance on the RUC.

4. Develop a collaboration between primary care and non-health care business.

They are also urging three specific actions:

They have set up an electronic petition that people can use to urge the three major medical societies that represent primary care physicians to quit the RUC.

On Health Care Renewal, we have been trying to make the systemic problems with with the leadership of health care organizations less anechoic in the hopes that greater realization that these problems exist would lead to actions to solve them. The regulatory capture by the RUC of Medicare's payment setting mechanism is one problem that really cries out for a solution. In 2007, I called for "an unbiased re-evaluation of the components of the RBRVS by people who are dedicated to doing it fairly, not benefiting one group of physicians, or the organizations that benefit from the increased use of procedures"; and "an unbiased investigation of what went awry with the process used by Medicare to determine physician payments." Your heard it here first on Health Care Renewal. It is nice to now have such distinguished company.

I urge our readers to consider the actions urged above.

True health care reform will require a transparent, honest, fair process for governments to decide on how they will pay for physicians' care and other health care services and goods.

Now there is a movement afoot to replace the RUC. In a new post on the Care and Cost blog, and the Replace the RUC site, Paul M. Fischer and Brian Klepper urged four approaches:

1. Make the public aware of the RUC’s role and urge the primary care societies to stop “enabling” the RUC through their participation.